Saturday, June 16, 2007

Despues de Guatemala...

- Flew from Guatemala to Edmonton, Canada for the wedding of my best friend from high school, Bridget. I stayed a week before the wedding, meeting the groom's family, helping get things organized, and just laughing it up with Bridget and her amazing husband-to-be. I saw the Aurora Borealis, experienced Canadian country-bar nightlife and danced the night away at the reception with Danny (who I got to see again after only two weeks!). I then flew BACK to Guatemala to prepare for the last two weeks of class and finals.

- After school was completed I collected my things, said goodbye to my CIRMA classmates and adios to Guatemala. I spent the next three weeks reacclimating myself to American culture (I am still amazed by grocery stores), relearning to drive, and reconnecting with my family and Danny. For some reason my usually very social demeanor went into recluse mode and I saw only a few friends. I worked a little, but mostly tried to organize and prepare myself for the next adventure I was about to start: Teach for America.

- Three weeks after returning home I left for Teach for America training, a program that trains recent graduates to become teachers and places them in low-income, high-demand, inner-city schools in order to close our nation's achievement gap. (Take the time to click on that link to educate yourself about the gross inequities in our educational system.) I am currently in Atlanta, Georgia with 400 other corps members training. What does training entail? Think: teacher boot camp where 4 years of education major classes are shoved into 6 weeks of hands-on training while you are teaching in an Atlanta public school trying to get your students to pass a high stakes test that determines whether or not they move on to the next grade. I haven't slept much. But it is already more rewarding than most of the work I did in college. I feel like this is where I need to be, and the more I learn about what this will entail, the more I feel like this is the challenge and issue I am should be working on.

- The next step? After training, I will be moving home to Phoenix (YAY!) and teaching 5th grade in the Roosevelt School District. I can't wait meet my students and start pushing them forward. Which is fine that I can't wait, because I will only have one week home before I start teaching.

I hope all is well with everyone and I hope to be able to talk soon (but probably not until I am back home in Phoenix). Best Wishes! Until my next adventure update, Bonnie

Friday, April 20, 2007

Semana Santa "Holy Week" in Guatemala

Piece #2: When we crossed the border into

It was especially intriguing to note the dissenter psyche of the people persevering in the capital city of

With our ex-guerilla fighter and marxist professor, we visited the Museo de la Voz y la Imagen, which is dedicated to maintaining the history of the civil war (with no help from the government which has no museum or dedication to the war). Seeing photos of the horrifying massacre in the pueblo of El Mozote was intensely haunting and compelling. Among such disheartening images and histories, I was impressed by the way in which the museum director spoke about the events. She presented the exhibition and repeated one theme over and over: the importance of remembering what happened so that it would not happen again. This hopeful understanding of her purpose within the museum and her duty to the future and past generations of Salvadorians was commanding and I admired her sense of purpose.

What impressed me most was a F.M.L.N. (the political party created from the revolutionary efforts of the 80's) legislative tribunal in the central

Our final day in El Salvador we rode in the back of a pickup truck and trudged on foot through the rough Guazapa hills to visit the base camp and strong hold for the revolutionaries during the war. As we passed over rotten and weathered old boots, tin cans, and bullet shells – remnants of the fight there – we were guided by an ex-guerilla fighter named

Our professor had this to say about our experience, “What you saw was a great achievement for

What the World Wants Most

In the dining room of my home, with leftovers of dinner spread out over the flowered table cloth, laced doilies covering every visibly flat surface, and strange figurines peaking out from the silverware cabinet, Victoria and I sat talking about her childhood.

Henry drove us through the foggy, curving hills surrounding Quetzaltenango and talked about how he had learned English, a story which I have heard over a dozen times. He worked in the

I met my friend Vinicio through the magic of music. Every morning I woke up to reggaeton thumping through my bedroom wall and decided that I needed to meet the mystery neighbor behind the hip-hop beats. I was greeted by a genuine mustached smile, English gangster slang and South Side LA tattoos covering most of his body. As we swapped music, we swapped stories and I learned that he had been in jail for the past three years (his second time) and that he had been let out early. He told me his story with as much honesty and sincerity as one could imagine. He didn’t hide anything; the good or the bad. Vinicio was born in

Everywhere that I have visited in the world, people are all saying the same thing: “We want a safe home, we want a loving family, we want true friends.”

Monday, March 19, 2007

Photo Recap of February and March

After four long weeks from my last entry, you can imagine how much has happened and how impossibly lengthy this entry would be if I summarized my experiences like I normally do. So instead of bombarding you with a short novel, I will give a photo recap of the past month, and you can see parts of it first hand:

My room. This is an important photo to show first because it is actually where I spent most of the past month. I’ve been sick for the past four weeks, longer than ever before in my life and I didn’t have the energy to keep up with the blogging (thus my hiatus). After two doctors, one radiologist, one wrong diagnosis and prescription, one CAT scan, one ear infection, one bout of pinkeye, and more sleepless nights than I care to count, I am glad to say that the bronchitis, allergies and nasal infection are starting to go away. I am more frustrated than anything else because I have spent three weekends idle and missed out on travel opportunities. However, as you will see, there was a ton to see and do in

My room. This is an important photo to show first because it is actually where I spent most of the past month. I’ve been sick for the past four weeks, longer than ever before in my life and I didn’t have the energy to keep up with the blogging (thus my hiatus). After two doctors, one radiologist, one wrong diagnosis and prescription, one CAT scan, one ear infection, one bout of pinkeye, and more sleepless nights than I care to count, I am glad to say that the bronchitis, allergies and nasal infection are starting to go away. I am more frustrated than anything else because I have spent three weekends idle and missed out on travel opportunities. However, as you will see, there was a ton to see and do in  Mariachi’s at a CIRMA celebration to welcome the stolen baby Jesus back to the nativity scene. This is apparently a tradition all over

Mariachi’s at a CIRMA celebration to welcome the stolen baby Jesus back to the nativity scene. This is apparently a tradition all over  The yellow house that Laura and Kendal are sitting in front of is my home in

The yellow house that Laura and Kendal are sitting in front of is my home in

Check out the fireball in the sky next to the church. Behind those clouds is Volcano de Fuego which erupted the other night. You could see the lava and fire shooting out of the mouth from

Dancer at cultural festival with beautiful smile.

Cultural dance festival on the steps of the Cathedral

That is a circus lion, leopard and jaguar being transported to the next fair grounds. It was raining and the lion was pacing back and forth while the truck blasted down the road at 70 MPH.

With my own kind. He wanted to play with my water bottle and was surprisingly strong. After interacting I’ve decided that I really want a tail. Really.

The beach front hotel we stayed at in

The beach in Playa

This is the river that separates

Laundry hanging in the garden at my home. In the background you can see the statue of Mary and Jesus with fruit and incense offerings.

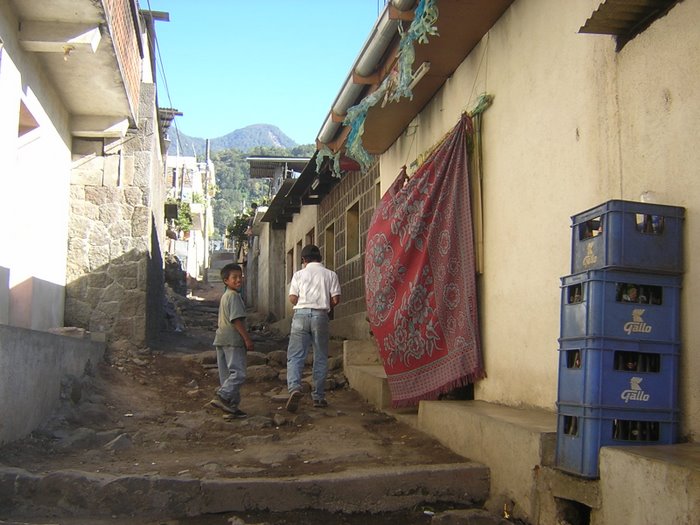

Laundry hanging in the garden at my home. In the background you can see the statue of Mary and Jesus with fruit and incense offerings. Calle Chipilapa with families out in front of their homes creating carpets from fruit, leaves, pine needles, and colored sawdust for the processional to walk over. The weeks leading up to Easter are a huge celebration with processions winding through

Calle Chipilapa with families out in front of their homes creating carpets from fruit, leaves, pine needles, and colored sawdust for the processional to walk over. The weeks leading up to Easter are a huge celebration with processions winding through  Luis, the grandson of my host family in front of the alfombra or carpet which I was able to help create.

Luis, the grandson of my host family in front of the alfombra or carpet which I was able to help create.

The procession passing by our house. The atmosphere of the crowd is comparable to a Fourth of July celebration in the states; complete with families, kids, vendors, sweets, balloons, popcorn and cotton candy.

My family: Luis (grandfather of little Luis), Victoria, and Maria Luisa, watching the festivities.

The processional bearers in costume.

The sheer mass of the processional is incredible. The men and women who carry it on their backs clench their teeth and fight to keep moving. Penitence doesn’t get more plain than carrying a thousand pound representation of your God on your back.

Cerro de la Cruz, on a hill over looking

Cerro de la Cruz, on a hill over looking

Just so you understand how big this cross is that is me at the base of the cross in the second picture.

Our second class trip to Maya ruins, this time in the capital city. The tin roofs to the bottom left are protecting the ruins, in the background the city. My fantastic archaeology professor Erick Ponciano is waving.

I’ve seriously thought about this tail thing. I want one. The beautiful painted Maya pottery in the Popul Vuh museum.

The sunrise by canoe at the wildlife preserve in

Marshlands

White cranes and the sunrise.

Waves from passing boat.

Reflection of sunrise...

Fishermen in the perserve getting food for the day.

Last weekend hanging out at the black sand beach. The water was warm and current crazy strong.

Monday, February 26, 2007

"I never let my schooling get in the way of my education" - Mark Twain

If my purpose for being here seems a little indistinct, it’s probably because I’ve yet to mention it at any good length. So let me clarify. I am here to learn. I am taking classes in the traditional form at CIRMA (Centro de Investigaciones Regionales de Mesoamerica), as well as absorbing the informal education that presents itself to all travelers. I am taking four official classes: History of Central America, Archaeology of the Maya, Literature of Central America, and Conversational Spanish. In addition, there is a colloquium series where some of Guatemalan’s finest and most distinguished minds speak to us (eight incredibly lucky students) about their areas of specialty. Outside of these classes, I have been taking private Spanish lessons twice a week with the daughter of my host family (she previously worked at one of the numerous language schools here in Antigua). Needless to say, with all of this packed into three school days (Tuesday through Thursday), and the traveling nearly every other weekend – I am busy. The free time I do have is spent at the gym at salsa-aerobics or writing and drawing.

Instead of outlining details of each class, I will give you excerpts worth repeating:

This past weekend our archaeology class went on a trip to Takalik Abaj, a Maya site from the Preclassic period in Southern Guatemala. Our professor, Dr. Erick Ponciano (an archaeologist who is leading a project in the Peten) and another archaeologist leading the Takalik project site explained the significance of the details, which made it much more worthwhile. We were allowed to go behind the scenes because of Erick’s ties to the archaeology community, and were able to watch the excavation of newly discovered pottery and hold a few pottery shards in my hands (over 2,500 years old!). (After this we made for a quick trip to the beaches of Chiapas, Mexico.)

This past weekend our archaeology class went on a trip to Takalik Abaj, a Maya site from the Preclassic period in Southern Guatemala. Our professor, Dr. Erick Ponciano (an archaeologist who is leading a project in the Peten) and another archaeologist leading the Takalik project site explained the significance of the details, which made it much more worthwhile. We were allowed to go behind the scenes because of Erick’s ties to the archaeology community, and were able to watch the excavation of newly discovered pottery and hold a few pottery shards in my hands (over 2,500 years old!). (After this we made for a quick trip to the beaches of Chiapas, Mexico.)In our first colloquium meeting, Tani Adams, the director of CIRMA and head of CIRMA’s latest social awareness project called “¿Porqué estamos como estamos?” (Why are we the way we are?), spoke with us on perception of classes in Guatemala. Tani is a perfect of example of what this project is dedicated to – showcasing the vast diversity of the Guatemalan population and shattering preconceived notions of what it means to be “Guatemalan.” She is a blue eyed light skinned, fifth generation descendant of German farming settlers to Guatemala, was born in Guatemala, speaks Spanish, English and German and has U.S. citizenship (her father is American). She is a Guatemalan through and through, the product of an interesting part of the country’s history, and yet wherever she goes people assume she is a tourist. She is accustomed to having to defend her nationality on a daily basis, because there is no place for her in the national psyche’s conception of identity. Instead the Guatemalan world is divided into only two types of people: Ladinos (non-indians) and Indians. The racism which created this subdivision is continued today in subtle and not so subtle ways (there are elite Castellan families that to this day maintain blood charts, “proving” that they are untainted by indigenous blood). She explained this history of polarized thinking by asking us to list perceptions of “civilized” versus “uncivilized” peoples. This is what we came up with (and let me preface this list by saying that discussing perceptions of racism or even reasons, isn’t the same thing as condoning or accepting it, on the contrary it is to better understand and self-reflect on personal short-comings in order to change perceptions):

Ladinos /Indians

Ladinos /IndiansCivilized /Backwardness

sophisticated /barbaric

educated /uneducated

industrious /lazy

rich /poor

clean /dirty – untouchable

healthy /sick

rapid /temporal

science /magic

logic /intuition

progress /stagnant – traditional

leader /follower

adult /child

male /female

citizen /subject

Culture* /culture*

*Culture with a capital C is used to signify “high culture” (ballet, symphony, opera, etc.), whereas culture with a small c is used to signify “low culture” (basket weaving, tortilla making, etc.); the “culture” that tourists come for. These perceptions of culture (little c) combined with the other elements on the list help to create a nostalgia and sense of loss for the “uncivilized other.” Tani formerly worked in D.C. as a lobbyist and said that the three issues which people responded to most (when fliers were sent out) were saving the whales, forests and “Indians.” Take a minute to think about the disparate lumping of these three things together. This sense of needing to “save the Indians” (who in reality have defended their own rights, passed revolutionary legislation in Guatemala allowing self-governance, and recently made huge political advances – Rigoberta Menchú, an indigenous woman, is running for president in this year’s upcoming election) is an idea created and perpetuated by the romanticizing of indigenous cultures. But in reality the profile or population that most needs help in Guatemala are young urban men with tattoos, because these men are the most likely to be discriminated, brought into the dark drug-world, and die early. But would people respond to a flyer asking for money to help this population? Probably not. It doesn’t fit within the prepackaged framework of who should be helped. This isn’t to say that discrimination of indigenous people and inequalities doesn’t exist, because they do (the changes recognized between the social imaginary and social consciousness are certainly different), but work combating racism is happening. Challenging people to think about race relations in these terms will hopefully reveal some uncomfortable truths and motivate changes. I am proud of the work CIRMA is doing.

Switching to my history class, Professor Jose Antonio who was a former guerilla fighter with the FMLN in El Salvador characterized the people’s reasons for the social revolutions of Central America in unforgettable way. Pacing in front of that class, speaking in first person, he takes on a persona and with an intensity glimmering in his eye he says: “I work hard. All week long and all day long I work hard. I work to feed my woman and the children. All week I work and at the end of the work day I need to have a few drinks to make the work disappear from my mind. So I drink and I drink. And when I start missing my wife, I go home to her.” At this point his voice gets dark and deep, flexing machismo in his voice, and he stops pacing, “And that stupid woman who has been doing nothing all day, nothing but staying at home with the children, she says she is tired and won’t come to bed with me… So I have to beat her.” He says this last point as though it is the only clear logical conclusion, and a chill runs up and down my spine. I begin to believe in the character that my professor has created (my professor who is infinitely sweet and righteous) and I am afraid of him, because I know that there are men who think like this all over the world and he convincingly portrays this man. I suddenly see the intensity that every ex-fighter holds within. He continues, “I have to beat her to show her that she will respect me. Because I am the one who provides for her and the children.” He bangs his fist on the table, “I am the one in charge of this house. I am the one who gives her money for food. I am the one who does everything. So I must beat that stupid woman to show her I am right.” Breaking out of character, he resumes his natural gentle manner and asks us, “And after night after night of this pattern, do you know what happens? It happens all the time. One night the woman waits quietly for her husband to go to sleep. And she sneaks into his bedroom and is very quite. She uses a knife from the kitchen and she slits his throat. She kills the man who beats and represses her.” He sits down, “This is the same with revolutions and dictatorial nations.” I understand his past history, and his countries rebellion against Romero. His characterization of subjugated citizens as the battered housewife and tyrannical governments as the abusive husband is both powerful and compelling. It speaks to the multiple levels of violence of these countries; the individual violence behind closed doors and the organized uprisings against cruel governments.

Switching to my history class, Professor Jose Antonio who was a former guerilla fighter with the FMLN in El Salvador characterized the people’s reasons for the social revolutions of Central America in unforgettable way. Pacing in front of that class, speaking in first person, he takes on a persona and with an intensity glimmering in his eye he says: “I work hard. All week long and all day long I work hard. I work to feed my woman and the children. All week I work and at the end of the work day I need to have a few drinks to make the work disappear from my mind. So I drink and I drink. And when I start missing my wife, I go home to her.” At this point his voice gets dark and deep, flexing machismo in his voice, and he stops pacing, “And that stupid woman who has been doing nothing all day, nothing but staying at home with the children, she says she is tired and won’t come to bed with me… So I have to beat her.” He says this last point as though it is the only clear logical conclusion, and a chill runs up and down my spine. I begin to believe in the character that my professor has created (my professor who is infinitely sweet and righteous) and I am afraid of him, because I know that there are men who think like this all over the world and he convincingly portrays this man. I suddenly see the intensity that every ex-fighter holds within. He continues, “I have to beat her to show her that she will respect me. Because I am the one who provides for her and the children.” He bangs his fist on the table, “I am the one in charge of this house. I am the one who gives her money for food. I am the one who does everything. So I must beat that stupid woman to show her I am right.” Breaking out of character, he resumes his natural gentle manner and asks us, “And after night after night of this pattern, do you know what happens? It happens all the time. One night the woman waits quietly for her husband to go to sleep. And she sneaks into his bedroom and is very quite. She uses a knife from the kitchen and she slits his throat. She kills the man who beats and represses her.” He sits down, “This is the same with revolutions and dictatorial nations.” I understand his past history, and his countries rebellion against Romero. His characterization of subjugated citizens as the battered housewife and tyrannical governments as the abusive husband is both powerful and compelling. It speaks to the multiple levels of violence of these countries; the individual violence behind closed doors and the organized uprisings against cruel governments. In my literature class I am reading “The Inhabited Woman,” by Gioconda Belli, which I suggest you read if you are at all interested in an honest portrayal of a woman’s emotional description of her world. It deals with the revolution in Nicaragua and her involvement in the movement. I wish I could write like her. I also read “One Day of Life” by Manlio Argueta, which is harrowing, but worth a read if you are interested in Central America.

In my literature class I am reading “The Inhabited Woman,” by Gioconda Belli, which I suggest you read if you are at all interested in an honest portrayal of a woman’s emotional description of her world. It deals with the revolution in Nicaragua and her involvement in the movement. I wish I could write like her. I also read “One Day of Life” by Manlio Argueta, which is harrowing, but worth a read if you are interested in Central America.Another speaker who came to our colloquium was Dr. Ricardo Stein, the brother of the Vice President of Guatemala who has a PhD. in Mathematics, works in politics and is quite possibly one of the most intelligent people I have ever met. He spoke with us about the 1996 Peace Accords that officially ended the war and established a new government in Guatemala. He was on the creation committee of the peace accords and discussed candidly the accomplishments and shortcomings of the document now that ten years have passed. The points that I took home from this living genius were his comments on corruption. He stated that corruption would not exist if it was not beneficial or functional to the system.

He explained that corruption could be a positive an effective tool in the hands of the right people, or a destructive and regretful tool in the hands of the wrong people. He believes that true change comes from the individuals manning the institutions. I would have to agree.

He explained that corruption could be a positive an effective tool in the hands of the right people, or a destructive and regretful tool in the hands of the wrong people. He believes that true change comes from the individuals manning the institutions. I would have to agree.As far as things that I have learned outside of class, the list goes on and on. I’ve learned to love thick corn tortillas. I’ve learned that I will never be fluent in Spanish, but that I can keep working on becoming functional. I’ve learned that it is more expensive to wear traditional clothing for indigenous people than imported clothing. I’ve relearned that children are truly the best way to break the cold ice that adults enclose themselves in. I’ve learned to appreciate the platonic friendships allowed between men and women in the U.S. And in turn, I’ve learned to hold my tongue and practice patience when talking to machos (which doesn’t mean I don’t despise it). I’ve learned that family is the most important value everywhere. And that Quetzaltenango, Guatemala makes the best hot chocolate in the entire world.

Until next time, Bonnie

Wednesday, February 7, 2007

Que Tengo Miedo

It wasn’t from the numerous bulges in the small of men’s backs (which I realized were guns) as we loaded ourselves onto the bus to Río Dulce like cattle. I just rationalize that this is a natural reaction of people for their own safety from gangs in light of the fact that 80% of all drugs in the

I wasn’t scared for my life from the eerie sounds of howler monkey calls that woke me from a dead sleep at the jungle hotel. (They are so loud the sound can carry for three miles!)

It wasn’t from the horse which I lost control of and nearly bounced me off as it ran unevenly at full pace over a steep hill on the 500 acre finca (farm). I got a hold of him and pulled back hard on the reins, and readjusted the uneven saddle. We gave the horses (and ourselves) a break and walked through part of the jungle canopy tour on elevated bridges a hundred feet above the creek. Then we climbed the stairs to the top of a tower that looked out over the lake and vast farm.

I wasn’t scared for my life from the two hour motor boat ride from

It wasn’t from the washed-up four feet long snake which I nearly inadvertently stepped on at the beach or the dead sea-turtle and numerous jellyfish. The beach at Lívingston was littered and dirty, but still beautiful. And our trip to Siete Altares, a series of seven waterfall pools did not disappoint. There were tons of locals cliff diving into the biggest pool, and after the long humid walk to the spot, I didn’t care that I had no swimsuit and jumped in with jeans and bra. The cold water was fantastic and the sunlight was beautiful as it filtered through the trees and sliced a few beams of light through the water. As we got out of the pool to dry off, we (Laura, Chrissy, Kendal and I) couldn’t help but laugh at the prepubescent machismo of a group of five 12 or 13 year old boys. So far the four of us have all experienced enough cat-calling, whistling and hissing to fill Santa’s goodie bag three times, but not from children! One boy swam over to us and asked me where I was from, and then commented that my physique didn’t look like I was from America, more like I was from Australia - as if he was an expert in the female form! As he and his friends blew us a parting kisses, I caught one, looked at it, and let it slip out of my fingers into the stream and they all burst out laughing. At least at this age, they can laugh at rejection – I’ve gotten a few angry stares from men when I react with anything but passive ignorance (which BELIEVE me is a test to my will-power every time).

It wasn’t from following the overly-gregarious and slightly-shady man who led us to “da-best dance-club-on-da-beach-don-worry-I-show-you.” It turned out to be a legit club right on the beach with locals, Guatemalan travelers, one other Gringo and traditional punta dancing (think hips and knees). The shady man of course wouldn’t leave until we fulfilled his demands of payment for his services, but it was an incredible experience. In the middle of the dance floor a local guy grabbed a glass coca-cola bottle (Laura said it right: You can count of taxes, death and coca-cola) and spun it as the entire club circled around and individuals were picked to dance alone in the center. Everyone participated and danced regardless of who they were, male or female, and everyone was immediately shuffled from their groups – blacks standing next to indios standing next to ladinos standing next to gringos. Everyone watched and laughed and no one was made to feel better or worse than the last who danced (and let me tell you that this is remarkable seeing that white-man syndrome seems exist everywhere – Not to perpetuate a false stereotype, but - why do white men have no rhythm? And why do black men have it so naturally?).

I wasn’t scared for my life from the packs of dogs which snarled threateningly at us as we walked home in the deserted night streets after dancing my feet into oblivion.

I wasn’t even scared for my life from the remains of three completely decimated semi trucks that we passed as we barreled and dodged cars along the windy cliff-lined roads back to Antigua (although maybe I should have been). We chose to get a private shuttle, because our experience on the public bus to Río Dulce took a 5 hour trip and turned it into an 11 hour trip. We stopped every half hour to stockpile more bodies into the main isle (we were incredibly lucky to have assigned seats) and to refuel by holding the gas can with funnel higher than the tank. The family that drove us back in our private shuttle was adorable. I don’t know how the husband was able to put up with the crazy antics of the drivers around him knowing that his young wife and year and a half old son were sitting in the seat next to him. I commend anyone who is able to safely drive in a third world country, and even more I commend the small children who so patiently sit there against their will without crying or fussing. The little boy was adorable. His sweet face and smile reminded me of my cousin Dillon, only with light brown eyes instead of piercing blue ones.

None of these things are what scared me to the core.

No, it was after the incredible weekend to the river town of

And what’s more frightening, and this sounds absolutely terrible in every possible way, but if something like this were to happen and I did survive, I would be reduced to the same level of helplessness and immobility as the people here. I would not receive special medical attention, the American embassy would not come and save me, and my money wouldn’t even help me. The bubble of safety which my skin tone, nationality and wealth quite normally afford me would disappear and I would truly know what it is like to be in an impoverished state. But even this would be temporary, because I would be able to return to the security and wealth of my homeland and leave the desolation behind me. I understand now why 1/5 of the Guatemalan population lives in the

Just to give you a picture of what I am referring to, my guide book summarizes the grim facts saying; “A Guatemalan maya can expect to live a life of 48 years, and a ladino to live to 66.” What is the difference between a maya and a ladino? Skin tone and language. Maya are indians speaking Mayan languages and a landino is everyone else. To give you a face to this statistic, my host mother Victoria (a ladino) is 57, and like I wrote before, her body is that of a 70 year old; she went yesterday to the dentist and had five teeth pulled that were falling out of her jaw. According to this statistic, she has 9 years left. The book goes on to say, “these statistics are some of the very lowest in the world, rivaling only those of AIDS-ravaged sub-Saharan Africa and

I am acutely aware that I am always separate from these people. I can only look into their lives from an outside perspective and never really understand what it is like to be in their shoes. After traveling to some of the most impoverished countries in the world, I sort of feel like all travelers to third world countries are spectators to a sort of poverty zoo. We go to see the culture (*with a little c), people and places not realizing how separated we are from the people we are standing right next to. For example, after only four weeks in

In Lívingston, I had a two hour conversation with Ignacio, a guy my age who worked at the hotel. I asked him if he had ever been to

I guess that is where I am right now. I feel the weight of all those around me and it isn’t a load that a single person can lift on her own. I feel the internal pressure of wanting to DO something, but what can one person possibly do that hasn’t already been thought of by the people who live here everyday? I suppose that writing these anecdotes and sharing my experiences with you all could help in some minute way. Ultimately, I guess it comes down to the fact that their will always be suffering in the world, and conversely there will always be joy. Like I said before, these people have nothing but eachother throughout their short lives and yet maintain a sense of appreciation, hope and gladness. Or so I perceive. I just wish that those who have so much more time and wealth would realize their gifts and fully appreciate the auspiciousness of their bounty; because the rest of the world surely does.

Monday, January 29, 2007

This is Antigua

Walking late at night in the lamp lit sidewalks with the crisp night air swirling down the empty cobblestone streets. Trying to cross the street while tuk-tuk’s fly by with their lawn-mower engines pattering loudly and single headlight lighting the way. Hesitantly stepping out into the mix of traffic (horse-drawn carriages, man-pulled carts, chicken buses, motorcycles, and

Walking late at night in the lamp lit sidewalks with the crisp night air swirling down the empty cobblestone streets. Trying to cross the street while tuk-tuk’s fly by with their lawn-mower engines pattering loudly and single headlight lighting the way. Hesitantly stepping out into the mix of traffic (horse-drawn carriages, man-pulled carts, chicken buses, motorcycles, and I have written all about my weekend excursions, but have yet to write anything about Antigua, so here are some slices of life from my hometown:

I bought a membership to a local gym, to keep all the frijoles and arroz (beans and rice) from doing too much damage, where I decided to try out an Aerobics class. And what a class! I have taken dance and work-out classes back in the States lots of times, but they were nothing like this one. “Aerobics” was really a non-couple version of salsa, with the students and instructor laughing and dancing the entire time. The music was banging, and you could barely hear the teacher speak (in English or Spanish), so to get our attention he would whistle, pat his head and use his arms to tell us what to do next. It was a blast. Definitely the most relaxed gym experience of my life; no one was trying to impress each other with their mighty moves or muscles, it was just fun.

Speaking of salsa… we checked out a dance club where all the locals go to dance and I was blown away. There was one couple that stopped me mid booty-shake (and you know how I like to booty shake), because I just had to watch them; they commanded and owned to dance floor. Salsa like I’ve never seen! The girl broke her heel mid dance, but did that stop her from doing the splits on the ground while her partner danced above her? Hell no! They were incredible, and after the salsa music switched to hip hop the guy challenged me to a dance off; much to his surprise I matched most of his moves. We both laughed and his partner came over to show me a few of the female salsa moves. It was a blast.

Here are some other experiences of Antigua:

-Being the only one who jumps every time celebratory fireworks go off in the street. (And this happens frequently. We are talking LOUD enough to be bombs, what a way to say happy birthday!)

-Teaching my host dad, Luiz, su-do-ku in Spanish; a true test of my Spanish skills.

- Watching the indigenous cows drive by in the street in front of my house on their final drive to the slaughter house.

- Sitting in the park and talking to teenage boys as they pull a prank with super glue on one of their friends.

- “Making” tortillas with

- Peering in one of the grand cathedrals and seeing at the very front of the church, on their knees in prayer, was a bride and groom taking their vows with their clans seated behind them.

- Watching incredibly elaborate religious processions, where 100 people hold up a memorial sculpture of Jesus on their backs and walk around the city, stopping at holy spots. (See pictures above)

- Reverently watching smoke plumes waft from the still active volcano Fuego (which means fire).

- Stepping foot into an old colonial hacienda which is now the largest and nicest McDonald’s I have ever seen. Can you believe it? I bet the original family never would have guessed that their elaborate home would one day become a fast-food chain.